Kirti Monastery

In 2008, a demonstration by monks from Kirti was fired upon by police, killing 23. Following the incident, 100 monks were arrested and military forces were stationed inside Kirti for nearly a year.

Tibet’s Buddhist monasteries form a key part of the country’s national identity. For Tibetans they hold great religious and cultural significance, and, under the Chinese occupation, they have also become centres of political activism. Due to their respected status, Tibet’s monks and nuns make natural community leaders. They run educational projects, orphanages and old people’s homes and help preserve Tibet’s unique culture and language. They also carry out protests. Monasteries are centres of Tibetan resistance.

China’s authorities see monasteries as a threat and have sought to break the bond between them and the communities that they serve. The methods may have changed – in the 1960s large numbers of monasteries were destroyed, whereas now they are put under surveillance and the inhabitants subjected to political re-education – but the struggle is ongoing. As one scholar puts it, Tibet’s monasteries have become “the principal battleground for Tibetan resistance to the Chinese state”.

“The local authorities are mistrustful and dislike the strong bond between monasteries and the lay people; they try everything possible to break that bond”– Exiled Tibetan

Monasteries have long been at the centre of Tibetan cultural, political and economic life. It was traditionally common for each Tibetan family to have relatives serving as monks and nuns, while monasteries also granted loans, financed trade and offered a safety net during economic crises.

The Chinese occupation put an end to this system. Monasteries were identified as rival power bases and intrinsically disloyal to China’s central government. Most were shut down. Things worsened under China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, during which time even private religious practice became illegal. Monasteries were destroyed in massive numbers and monks were jailed or forced into hard labour.

After more tolerant policies were introduced across China, monasteries re-opened, but with state controls over their religious activities that continue to this day. As outlined below, their freedom to teach, recruit monks and nuns and even appoint their own leaders are all restricted by China’s government. Images of the Dalai Lama – the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism – and copies of his teaching are banned.

In recent years, monks and nuns have faced a new threat to their way of life, as Chinese tourists come to Tibet in previously unimaginable numbers due to improved rail links and efforts by China’s government to promote Tibet as a tourist destination. Some monasteries have been renovated to turn them into tourist sites, or modified to create space for restaurants, hotels and shops. Monks have reported huge numbers of tourists coming to their monasteries on a daily basis, disturbing their studies and way of life.

“Since the Chinese government invaded Tibet in 1949, Tibetans have never stopped protesting and never accepted the Chinese government as our own government. In this process, we had fought with arms and many were killed, arrested and sentenced…”

– Kanyag Tsering, a monk from Kirti Monastery now exiled in India, 2016

Despite these restrictions and intrusions, monasteries have continued to play a pivotal role in resisting the occupation, representing what one scholar has called, “a Tibetan civil society, outside state control”, an “institution that Tibetans are able to identify as their own” that has “come to signify Tibetan nationhood and survival”.

Monks and nuns have frequently been at the forefront of protests and been closely involved in organising them, including major outbreaks of resistance in the 1980s and in 2008. In 2009, a monk called Tabe set himself on fire in protest against Chinese rule, launching a wave of more than 140 self-immolation protests across Tibet, almost half by monks or nuns. Others pass information about conditions in Tibet and protests by Tibetans to the outside world via Tibetans living in exile in India.

In response to threats to their language and culture arising from state control and Chinese immigration, monasteries also take a political role through actions intended to defend them. Monks conduct activities such as debates and classes in the Tibetan language and Buddhist philosophy for local communities. Others give lectures on cultural, political and environmental issues.

China’s approach to the threat posed by monasteries has two aspects: state intrusion into their day-to-day affairs and using the full force of its security apparatus against any sign of political activism.

Where once Tibetan monastic bodies had responsibility for the admission, training and teaching of monks and nuns, now Democratic Management Committees, controlled by the Chinese government, control the basic affairs of monasteries and nunneries. These committees also take decisions previously made by monasteries on reincarnation – a central aspect of Tibetan Buddhist institutions – attempting to dictate to Tibetans who qualifies as a reincarnate lama.

In April 2015, Chinese officials stated that Tibet’s Buddhist monks and nuns should dedicate themselves to the Communist Party as much as their religion, and that their monasteries should be centres of patriotism and fly Chinese flags. The former Party Secretary of Tibet, Chen Quanguo, claimed that this would guarantee “model harmonious monasteries”, and allow Tibet’s monks to “have a personal feeling of the party and government’s care and warmth.”

The Chinese government has also placed controls on how many monks can stay in a monastery, for example, cutting the number of monks in Labrang monastery in eastern Tibet from 3000 monks, down to 1000 monks. Security cameras have also been installed inside monasteries. Thousands of monks and nuns have been forcibly evicted from monastic towns such as Larung Gar in 2016 and Yarchen Gar in 2019.

When monks and nuns carry out protests, monasteries and nunneries can be shut down or face mass arrests. They may also be subjected to month-long political re-education campaigns, where monks and nuns are forced to agree that Tibet is an inalienable part of China and denounce the Dalai Lama, causing them great distress. Monks and nuns that have refused to sign documents denouncing the Dalai Lama and accepting China’s version of history have been detained, tortured and forced to leave their monastic institutions.

Individual monks and nuns face arrest, violence, torture and harsh sentences if they fall foul of the authorities. Under close surveillance in their monasteries, they may be arrested simply on suspicion of planning protests, or for showing signs of loyalty to the Dalai Lama. Those seen as community leaders can face jail on trumped-up charges for actions such as setting up Tibetan language classes. Those arrested and convicted for involvement in protests are often tortured.

In 2008, a demonstration by monks from Kirti was fired upon by police, killing 23. Following the incident, 100 monks were arrested and military forces were stationed inside Kirti for nearly a year.

Labrang Monastery has been one of the focal points of Tibetan resistance. Hundreds of monks joined a mass protest in Labrang in March 2008 - part of the wider uprising against China that year.

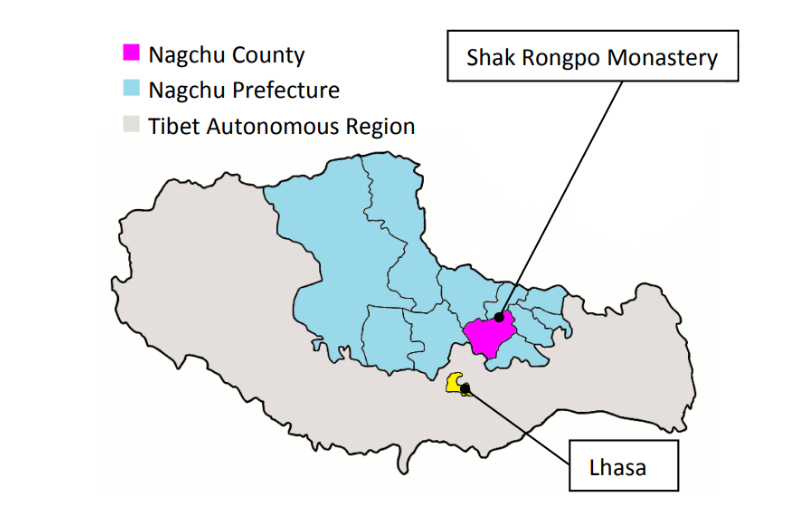

Historically Driru was a self-managed area for hundreds of years, not even identifying with Lhasa. In 2010 it became a centre for protests due to environmental exploitation by Chinese companies.

The nunnery was also targeted in the 2013 crackdown in Driru, with most of its nuns forced out. A political re-education campaign was also imposed on the nuns, who responded by going on hunger strike.

The monastery, established over 300 years ago, was subjected to severe repression from April 2010, along with the surrounding population, after members of the monastery were accused of contacting the Dalai Lama.

Free Tibet’s research partner Tibet Watch has published a comprehensive report examining the role of monasteries in defending Tibet – and the price they have paid in repression.

You can read the full report here, as well as the executive summary here.

[Content warning: the above reports contains graphic images of injuries that some may find distressing]